Unlock 10% off on your first order and gain access to exclusive, limited-edition projects.

WEAVING IN THE VALLEY OF GODS

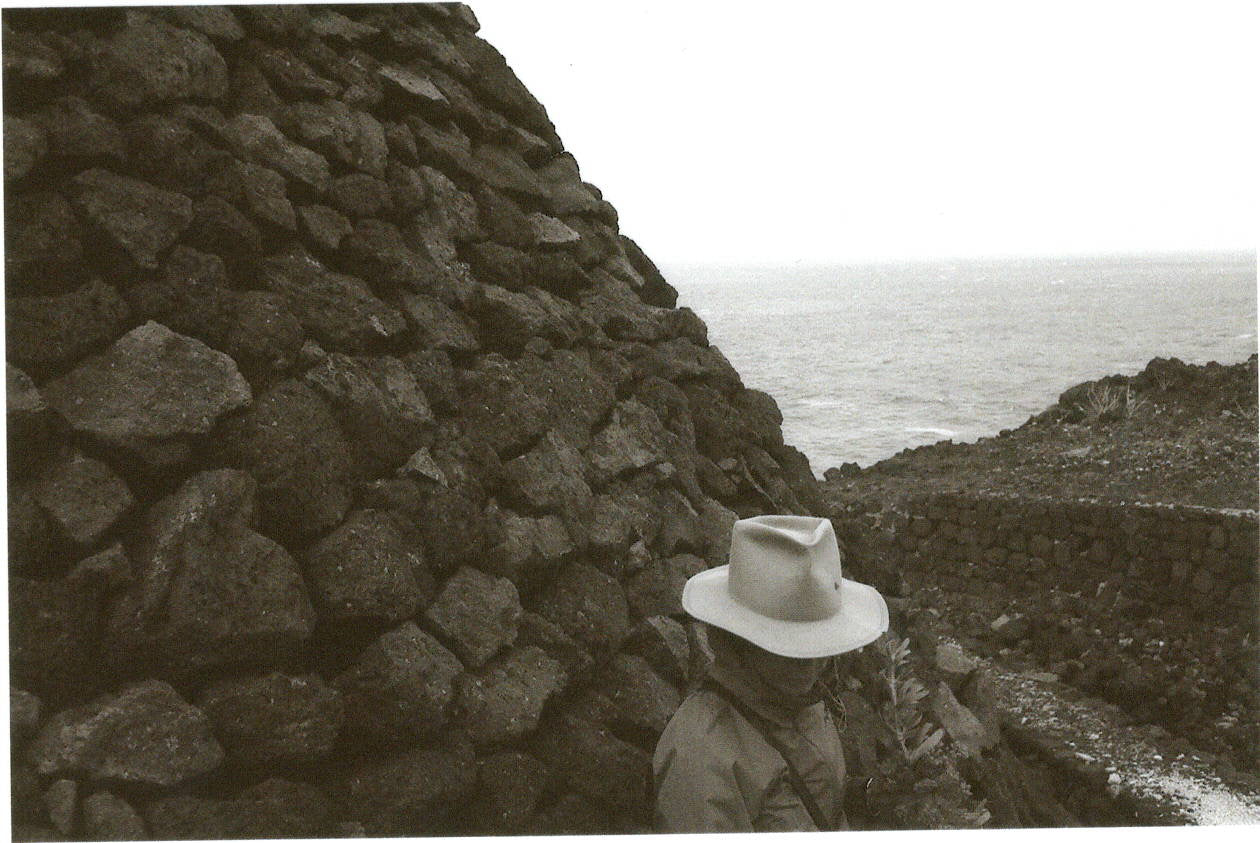

The Earthpiece Journal goes to India, where in a small town at the base of the Himalayas the importance of place is fundamental to the practice of Kullu handweaving.

Surrounded by snow-capped mountains descending into a river and an area rich in spiritual history, it’s no coincidence that the Kullu Valley is known as the Valley of the Gods. Positioned in the north of India in Himachal Pradesh, Kullu is also isolated and very cold, leading to a unique specialisation in the region.

Using wool from locally reared pashmina goats, sheep and angora rabbits, the people of the Kullu Valley have been hand-spinning their own yarn and handweaving their own cloth for garments for centuries. This tradition so centres in the town of Kullu, that at one point it even had the world’s largest angora farm; no mean feat for a town of 400,000 or so.

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Over time Kullu has become known for distinct products, including the Kullu shawl. Characterised by a predominately plain base in a simple weave or twill of often undyed fibres, these shawls are bordered with rich, geometrical patterns that are embroidered directly onto the fabric as it’s handwoven on the loom. Distinct to Kullu, this embroidery work is incredibly intricate, and so it follows that the value of the shawl increases with the width of the border. This kind of embroidery is also used as a trim for traditional woollen Kulluvi caps, and warm Pattu dresses for women.

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Today there are mechanised options for yarn and cloth production in Kullu, though handmade traditions live on. Kullu boasts 4,500 handlooms still in operation, most of which are old style frame looms requiring great skill to operate. Picture a piano where the warp on these frames acts as white keys; a fixed and stable strung base that’s elevated and eased with foot pedals, while the weft flies by in a shuttle, clacketing around as it weaves its way through the dulcet hum of the interchanging warp (the sharps and flats if you will).

Perhaps the most notable handweaving enterprise in Kullu is Bhutti, founded in 1944 when a group of 12 weavers in the area wanted to work together and share resources, evolving into what is today the Bhuttico Weavers Cooperative Society. The cooperative provides housing to its members, who are rather uniquely evenly represented across genders. While weaving is seen as a largely man’s occupation in most of India, in the region of Himachal Pradesh there is no gender bias for this work and at Bhuttico, all weavers are paid the same wage.

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Kullu handweaving is at once entirely traditional, rural and dates back to a pre-digitised – in fact a pre-industrialised – world. At the same time, there’s something very contemporary about this self-reliant practice. Initially not set up as an industry at all, but simply a way in which people in the community clothed themselves to keep warm, now it’s an industry of zero-kilometre clothing where the raw material is sourced and spun into yarn that’s then woven into cloth and worn, all in the same location. It represents a supply chain that’s almost unheard of in the global apparel industry, not to mention one that’s simple and honest.

And while this type of production may not be scalable into big business, it is scalable on an individual level. Kullu very much continues the vision of one Mahatma Gandhi; of a nation that’s self-clothing, self-reliant, and inherently sustainable. He saw an India in which everyone had their own simple handloom to produce their own clothing, instead of using mass-produced imported cloth that was threatening the very fabric of the nation.

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

Over the past year, pretty dire circumstances have led many people to handmaking skills, be it breadmaking, cooking or gardening, allowing for a little more self-reliance when perhaps previous options were less available. This elevation of at-home skills into self-sustenance is certainly of the time, momentarily loosens the chokehold of capitalism, and perhaps will evolve into more permanent handmaking habits; those that are inherently healthier for the planet. The name Kullu in fact comes from the term ‘Kulant Peeth’, meaning the ‘end of the habitable world’, though when the nature of habitation is in some ways reverting to age-old traditions that have far less impact on a fragile earth, perhaps this small town is in fact the beginning of a habitable world.

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

All photos by Hormis Tharakan