Unlock 10% off on your first order and gain access to exclusive, limited-edition projects.

A FOAMY FORAY

The Earthpiece Journal looks at chasen from Japan, the ornate yet robust companion to your matcha-drinking endeavours.

The way these whisks are made hasn’t changed in over 500 years, which can’t be said for most things. Lightweight yet laden with history, technique and hours of work, each chasen, as it’s called in Japanese, is a tool as much as it is a piece of art. Varying from 16 to 120 spines, each whisk is made from one piece of bamboo that’s painstakingly split and curved on one end to form the whisk.

Essentially this is a traditional bamboo utensil that’s used to evenly mix hot water and matcha, a concentrated and powdered Japanese green tea. Matcha doesn’t readily dissolve in water so it needs a bit of encouragement, and a lowly teaspoon isn’t going to do the job. Further, matcha should be frothy with tiny air bubbles lifting the flavour of the tea. And while these whisks are traditionally used in formal tea ceremonies, any layperson who enjoys matcha at home can, and perhaps should, use a chasen; if not for the taste then for the meditative practice it asks of you, and the froth that follows.

Traditional matcha whisks will always have a node in the bamboo that provides a natural boundary between the whisk and its handle, meaning choosing the right piece of bamboo is essential in the making process. If you’re interested, start with young bamboo that’s nimble enough to transform into a trustworthy whisk. This single piece of hollow wood is then split with a knife in progressively small, incredibly precise slithers (down to 0.1mm thick), and the top of the whisk is dipped into warm water to curl it inwards. Each time the whisk is subsequently used, it should be layed first in hot water to avoid the tips splintering, reminiscent of its beginnings.

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

The last step is separating the spines into an outer and inner layer with woven cotton thread, commonly black for practicality, just above the node. The cotton fixes the shape though you cannot ignore the fragility of the whisk and the delicacy of the spines that are totally at odds with the strength of the solid bamboo handle, despite one being an extension of the other. We all have two sides, but this is quite something.

In practice, the whisk should be used so that the tips scrape the bottom of the matcha bowl in a “W” movement, though should never be pressed down so to avoid bamboo shards floating in your matcha foam. This brisk whisk should take around 30 seconds, providing a focused and often essential pause to the day. The more prongs to the whisk, the lighter and airier your tea will be. It follows then that less prongs produce tea with a heavier taste and texture. 64 spines or prongs tends to be a healthy middle ground, or the Switzerland of whisks, if you will.

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

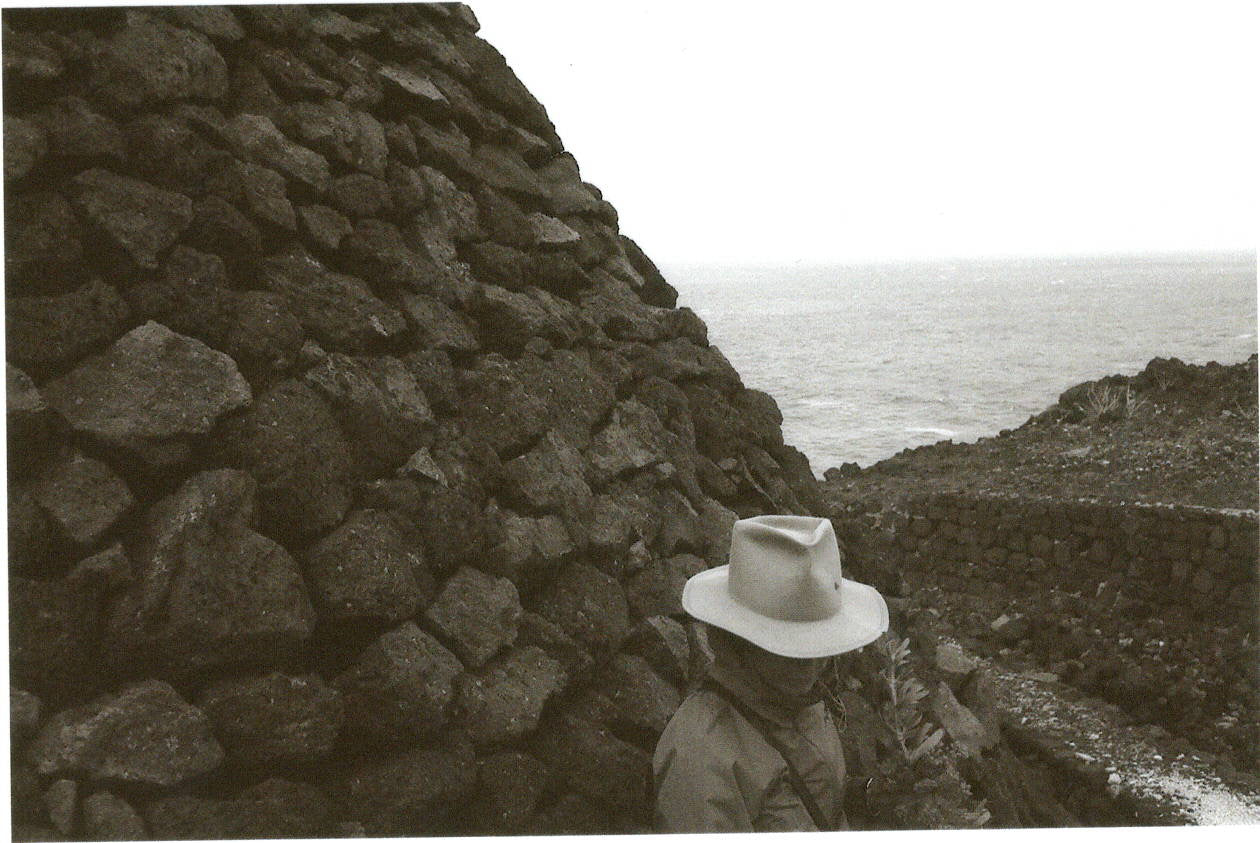

Almost all Japanese-made matcha whisks are made in Takayama, a small city close-enough to Osaka, by 12 masters and their studios (so the story goes) with the most famous being a studio called Chikurinen, which has been around since 1633. Over the centuries as emperors changed, earthquakes erupted, wars broke out and ended, somehow, wonderfully, the practice of tea ceremony persisted and the art of making matcha whisks continued. There’s a certain comfort in knowing that, despite everything, people will always drink tea.